The Digital Body: Radiology embraces the digital age

by Tom Mason

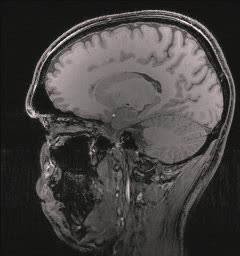

Dr. Rudiger von Ritschl scrolls through a series of computer screen images. As the slices of brain tissue peel away like the layers of an onion, an ominous, tentacled mass begins to emerge from the shadows. It’s a huge brain tumour, one that was an unrecognizable speck of discolouration on conventional x-rays, rendered glaringly obvious even to an untrained eye.

Dr. Rudiger von Ritschl scrolls through a series of computer screen images. As the slices of brain tissue peel away like the layers of an onion, an ominous, tentacled mass begins to emerge from the shadows. It’s a huge brain tumour, one that was an unrecognizable speck of discolouration on conventional x-rays, rendered glaringly obvious even to an untrained eye.

The device that Dr. von Ritschl and other Queen Elizabeth II Health Sciences Centre neuroradiologists are using is a relatively new technology called magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). In a technique that reads like science fiction, MRI uses a huge magnet 30,000 times more powerful than the Earth’s magnetic field to perform a feat of quantum mechanical gymnastics – forcing a significant number of hydrogen protons in the human body to align their “spin magnetic moments” in the same direction. Because different tissue types behave differently when subjected to magnetic fields, MRI scientists can create a computer picture of the soft tissues of the body in dramatic, three dimensional detail. “MRI gives us an exquisite picture of soft tissue,”says Dr. von Ritschl. “One we can’t get with any other technique.”

MRI, PET, SPECT and CT scans and other state-of-the-art tools have quickly become part of the vocabulary of medicine. In just the last decade, the science of radiology has changed so much that even x-ray film, the standard tool for 100 years is disappearing fast. Now QE II radiologists retrieve x-rays from digital storage devices and read them on a computer system called the Picture Archiving and Communication System (PACS). In many ways, PACS is the most exciting development to happen to our profession in a long time,” says Dr. Paul LeBrun, chairman of the Department of Radiology at the QE II.

Gone are the days when specialists jockeyed for possession of a single set of films. With the PACS system doctors can simply call up a patient’s x-rays on a computer screen in any hospital department, at a remote office location or even at home over the Internet. The radiologist’s report is attached to the chart, and doctors can use a special tool to draw or make notes directly on the x-ray without hurting it.

PACS allows radiologists to manipulate the contrast to bring out clearer images of critical areas. And most importantly, in a situation where timely treatment can mean the difference between a good and bad outcome for a patient, the PACS system is fast. PACS means that x-rays can be taken at one location and instantly analyzed hundreds or even thousands of miles away — an ability that may some day have significant benefits for patients and doctors at remote clinics or even in foreign countries.

Radiologists are taking over some of the roles traditionally reserved for surgeons, using tiny catheters and probes to perform some of the procedures that once required huge incisions and long recovery times. But the most fundamental change in the science of radiology may be just around the corner. Radiologists are starting to move beyond looking at the body as a series of still pictures and are beginning to look at the way the body functions on a cellular level.

The new powerful diagnostic techniques mean earlier detection of disease and that’s critical, according to Dr. von Ritschl. “As treatments improve, we must be able to diagnose disease earlier. This may improve survival rates dramatically.