Not your father’s forestry industry

by Tom Mason

IN MANY WAYS, GROUPE SAVOIE is a microcosm of the forest industry in Atlantic Canada. From humble beginnings 30 years ago, the family-owned business has mushroomed into one of the major players in New Brunswick’s $2 billion forestry industry, overseeing an operation that includes plants in Saint Quentin, Kedgwick and Moncton, New Brunswick, in Westville, Nova Scotia and in Jefferson, Tennessee. Not content to be mere harvesters and sawyers of wood, the company has evolved over the years into a value-added producer that cuts, cures, and processes hardwood into a host of products including hardwood flooring, components for cabinets, furniture and pallets – racking up numbers that currently include $100 million in annual revenues and nearly 600 employees spread throughout its multinational operations.

IN MANY WAYS, GROUPE SAVOIE is a microcosm of the forest industry in Atlantic Canada. From humble beginnings 30 years ago, the family-owned business has mushroomed into one of the major players in New Brunswick’s $2 billion forestry industry, overseeing an operation that includes plants in Saint Quentin, Kedgwick and Moncton, New Brunswick, in Westville, Nova Scotia and in Jefferson, Tennessee. Not content to be mere harvesters and sawyers of wood, the company has evolved over the years into a value-added producer that cuts, cures, and processes hardwood into a host of products including hardwood flooring, components for cabinets, furniture and pallets – racking up numbers that currently include $100 million in annual revenues and nearly 600 employees spread throughout its multinational operations.

“Wood is my world,” says company president and founder Jean Claude Savoie matter-of-factly. But lately that world has been changing fast. Downturns in industries from housing to newspapers have meant that many of the traditional markets for wood products have been in decline in recent years. Energy costs are on the rise, along with competition from other markets. Mills across Atlantic Canada and Maine are shutting down at historic rates. When the U.S. housing market began its historic slump three years ago, it was the forest industry, not the American banking industry, that felt the initial pressure. It’s not an easy time to be a forester in Atlantic Canada and Maine – not if you’re interested in sleeping well at night.

But if he’s worried, Jean Claude Savoie isn’t showing it. For him, these uncertain days are a time of major opportunity, maybe even the dawn of a new age of forestry. He says that despite its long pedigree, despite the fact that it is our oldest building material and our first fuel source, the potential of wood has been mostly overlooked until now. Trees are a vast storehouse of untapped potential, a source of everything from plastics to electric power – a 21st century industry just waiting to happen. “Right now wood is like oil was 100 years ago,” he says. “Back then oil was just a big gooey mess that came out of the ground. They had no idea all the things that would come from it, all the chemicals that could be processed from it. Today we even put it in our food.”

Savoie is certain that the same thing lies in store for the forest industry in his native province. That’s one of the reasons he signed on to the Atlantica Task Force on Bioenergy, a consortium of 22 forest industry, government and academic stakeholders across New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and Maine. The group recently tabled a detailed study of the future bio-energy potential of the region’s forests. The study, conducted by the consulting firm PricewaterhouseCoopers, analyzed the existing forestry industry in the international region known unofficially as “Atlantica” and identified potential industries that will work well with the existing infrastructure. In the end it made 15 key recommendations to jumpstart a new bioenergy economy in the region.

“The task force began out of a recognition that the forest industry in the Atlantic region needed new options,” says Bruce McIntyre, a forestry expert and partner with PricewaterhouseCoopers and one of the authors of the task force report. “It’s been in a long, slow decline for quite some time and the current economic climate isn’t helping at all. Nova Scotia, New Brunswick and Maine have got some very significant forest resources, but they are dealing with a combination of high labour costs, high operating costs and weak markets. The Atlantica report is a way to start the conversation about bioenergy.”

At the core of the report is an examination of 26 technologies and processes that currently exist – processes designed to streamline the bioenergy industry and to refine trees into useful products like electricity, plastics and commercial chemicals. The task force whittled those 26 down to six technologies and ultimately chose four of those – biorefining, value prior to pulping (VPP) for TMP operations, VPP for a hardwood kraft pulp operations and torrefaction – as appropriate technologies to kick-start the new Atlantica bioenergy economy. “We started with the fundamental hypothesis that businesses that have already invested in the industry are the most suitable businesses to develop biotechnology processes,” says Thor Olesen, the executive director of the Atlantical Bioenergy Task Force. “The four technologies we chose are ones that are intended to be integrated into existing industry.”

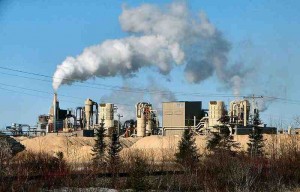

As usual, Groupe Savoie is already slightly ahead of the trend. The company already uses bioenergy in the form of sawdust, chips and bark from its mill operations to partially power its plants. It has a new product on the books, a pressed-wood brickette that it markets as a fuel for wood stoves and fireplaces, and is also tooling up to produce another value-added product – wood pellets. Unlike unprocessed firewood, the burning properties of pellets are nearly identical to coal, says Savoie. That means that electric utility companies like NB Power and Emera can use them to fuel their coal-fired power plants without the need for expensive retoolings.

Emera was one of the first stakeholders to sign on to the Atlantica task force. With a power generation network that includes electrical utilities in both Atlantic Canada and Maine, the company is already using green biofuel to partially power its giant Point Aconi generating facility in Cape Breton. Now it is studying one of the key technologies identified in the Atlantica Task Force – torrefaction. The process bakes raw wood into small, dense pellets, turning them into an ideal fuel for coal-fired generating plants.

Don Berringer is an engineer and consultant with Emera who has been involved with the Atlantica Task Force since its inception. He says that the torrefaction process has huge potential for the power company, providing a clean-burning fuel that burns well in pulverized coal generating plants. “The goal for us now is to partner with other stakeholders involved in the biomass industry, to find opportunities to get more value from biomass products.”

But Berringer says that relying on biofuel presents a delicate balancing act as well – one his company is determined to address. “Supply is one of the ruling factors. We have to be careful not to take someone else’s supply. That would elevate the market and make biofuel more expensive.” With that in mind, Emera is currently looking at underutilized tree species, small trees that have been traditionally ignored by logging operations and the waste products that end up on the forest floor at the end of a forestry operation as possibly sources of biofuel supply.

If generating green energy from trees and waste materials from the forestry industry seems like a promising trend, it’s only the beginning, according to Thor Olesen. The task force has also addressed something that maple syrup, eucalyptus and rubber producers have known for a long time – there are a lot of things that can be produced from trees. “When we talk about bioenergy, we’re talking about all the products that come from the forests as well,” Olesen says. “Products like carbon fiber, plastics, waxes, maybe even things we haven’t considered yet. There is no question that the chemical content of a tree can make all these products. The question we need to answer now is whether they can do it as cost effectively as other industries can.”

The 22 stakeholders who have joined the task force study all have a vested interest in answering that question. They are a diverse group, including universities like Dalhousie, University of Maine and University of New Brunswick, large companies like NB Power and AbitibiBowater, and interest groups like the Maine Pulp and Paper Association and the New Brunswick Forest Products Association. But what really gives the task force its teeth, according to Bruce McIntyre, is that fact that three governments from two countries are also key stakeholders. He says the international border the separates the two sides of Atlantica is an insignificant barrier when it comes to the region’s forestry industry. “There are more similarities than differences on the two sides of the border. The forest types are the same. The industries are the same. A lot of forestry companies have assets on both sides of the border. There are a lot of synergies here, and the only way this is going to work to its full potential is if we take advantage of those synergies.”

It’s a promising start. But there is only one way that the Atlantica Bioenergy Task Force will be truly successful, according to Olesen. “The real measure of success is whether real products come out of this or not. Right now we’re looking for funding so that we can continue this work and be the advocate for all 15 outcomes that are outlined in the report. The resounding endorsement from out stakeholders is that we have to continue what we’re doing. The bio-energy industry is blossoming around the world. There is a strong desire to see it happen here in Atlantica. Let’s continue this for three more years and see what we can accomplish.”